PDF - 2016 Annual Letter (pdf, 2.57 MB)

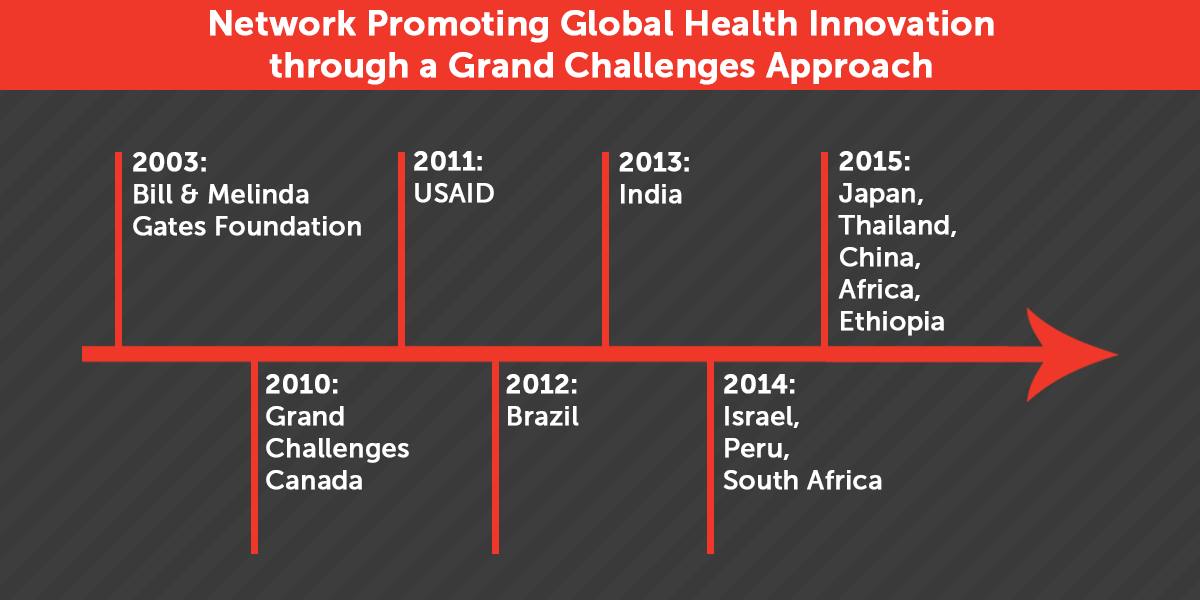

In 2010, Canada became one of the first countries to apply a Grand Challenges approach to international development by funding Grand Challenges Canada, with a focus on development innovation in global health.

Grand Challenges Canada was created to test new approaches to marrying development with innovation, in search of exciting new solutions to pressing challenges. We have spent the past six years testing, innovating and iterating. Although our approach is still a work in progress, we have learned a great deal and, in the process, have helped our innovators to develop solutions that save and improve the lives of the poorest of the poor in lowand middle-income countries around the world. Perhaps most important of all, we have refined a model that we think delivers on its promise: one that catalyzes innovation, unleashing Bold Ideas with Big Impact .

Consequently, I decided to use my letter this year to explore some of the insights and learnings from Grand Challenges Canada’s experience. In particular, I wanted to explore those ideas and approaches that might help to inform the work of others seeking innovative solutions to big challenges and measurable results.

In Makueni County, Kenya, I met a woman who shared her story of living with mental illness. She is now being helped by a Global Mental Health project supported by Grand Challenges Canada.

First, a quick refresher on who we are and what we do.

Since our creation six years ago Grand Challenges Canada, which is funded by the Government of Canada, has supported approximately 700 innovations in more than 80 countries. These innovations have the potential to save hundreds of thousands of lives, and improve millions of lives by 2030.

We work with a range of partners, both in Canada (the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada’s International Development Research Centre, and Global Affairs Canada) and internationally (the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Global Development Lab at USAID, and a network of other Grand Challenges initiatives).

An independent Summative Evaluation conducted in 2015 of the Development Innovation Fund in Health (DIF-H), which provides funding for Grand Challenges Canada, concluded that:

The Government of Canada’s investment in DIF-H has provided value for money. Investing in DIF-H remains relevant, and DIF-H has produced significant results. These outcomes have been produced economically, with acceptable levels of allocative efficiency and good levels of operational efficiency.

This kind of affirmation is incredibly motivating for our team. What excites us even more, however, are the individuals, families and communities whose lives are being transformed by the innovators we have the privilege to support.

These kinds of results, and the individual stories we hear on the ground, suggest to us that we are on the right track and are pursuing the right approaches. Thinking, in particular, about policymakers and program managers who are always on the lookout for models that provide real promise, I would highlight the following six lessons that we have learned over the past six years.

1. Focus Investment on a Grand Challenge

At its core, a Grand Challenge approach is a process for defining problems (“Grand Challenges”), building partnerships to find solutions, and managing and measuring progress. Its key elements are innovation with impact, partnerships and accountability for results. Over the past six years we have launched – alone or in partnership – programs to address three targeted challenges: Saving Lives at Birth, Saving Brains and Global Mental Health. The last challenge, Global Mental Health, is one of the most neglected of all global health challenges.

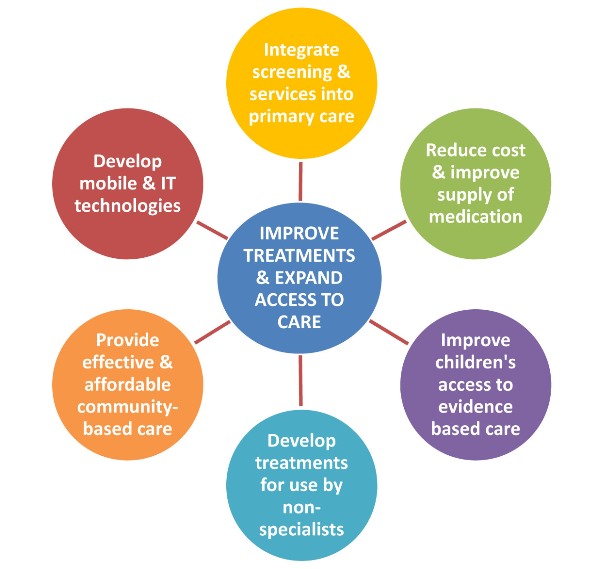

Areas of focus for Grand Challenges Canada’s Global Mental Health program

Mental disorders contribute 14% of the global burden of disease and 75% of this burden occurs in low- and middle-income countries, where scarce resources and a shortage of trained professionals mean that individuals living with mental disorders have limited access to evidence-based treatments.

Even in communities where treatment is available, the widespread stigmatization faced by those living with mental illness means that they are often unwilling or unable to access this care. That is why Grand Challenges Canada launched its targeted challenge in Global Mental Health. In a few short years, this program has helped to catalyze mental health as a global development priority.

The impact of this program was recognized in the recent United Kingdom All Parliamentary Group Report Mental Health for Sustainable Development, which stated, “The Canadian Government is funding the world’s largest body of global mental health research projects through Grand Challenges Canada”.

More importantly, tens of thousands of people are currently receiving mental health care through Grand Challenges Canada-funded innovations, with the potential to improve an additional hundreds of thousands of lives by 2030.

These treatments can greatly improve the quality of life of individuals living with mental health conditions, by enabling them to function effectively enough to do productive work, earn income and look after their households. Perhaps the most transformative element of this program is that domestic governments in low- and middle-income countries want and are willing to invest in evidence-based mental health innovations that can be implemented at scale. In the past, these evidence-based approaches were not available but that has changed, thanks to the results achieved by this program.

One example of a potentially transformative innovation supported through this program is the Friendship Bench. In many parts of Africa, if you are poor and mentally ill, your chances of getting treatment are close to zero. In Zimbabwe, that’s changing thanks to the Friendship Bench, the first project with the potential to make mental health care accessible to an entire African nation. It’s a simple idea: create a comfortable space where people can share their troubles with community members who listen compassionately and offer problem-solving therapy.

Developed by University of Zimbabwe psychiatrist Dixon Chibanda in 2006, the Friendship Bench project will reach 14,000 people, to reduce their symptoms of depression and anxiety and improve their quality of life. Funding from Grand Challenges Canada has positioned them to be the first model of mental health care in a community setting at scale on the African continent. This model also has the potential to be adopted by other countries in the region, leading to a transformation in how mental illness is diagnosed and treated.

In Zimbabwe, a trained health worker counsels a young mother on the Friendship Bench, through a project supported by Grand Challenges Canada.

2. Energize the Next Generation of Innovators and Social Entrepreneurs

One of the most welcome by-products of our model has been the opportunity to engage and energize the vast and largely untapped resource of social entrepreneurs, both in Canada and in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). In addition to attracting an entire new layer of on-the-ground entrepreneurs to the innovation pipeline, we’ve also had success in linking social enterprises in these countries with similar organizations here in Canada, fostering new networks and unleashing new channels of innovation. The following table highlights some of the Canadian social enterprises that have been catalyzed by Grand Challenges Canada funding. A similar table could easily be produced for new social enterprises that we have fostered in low- and middle-income countries.

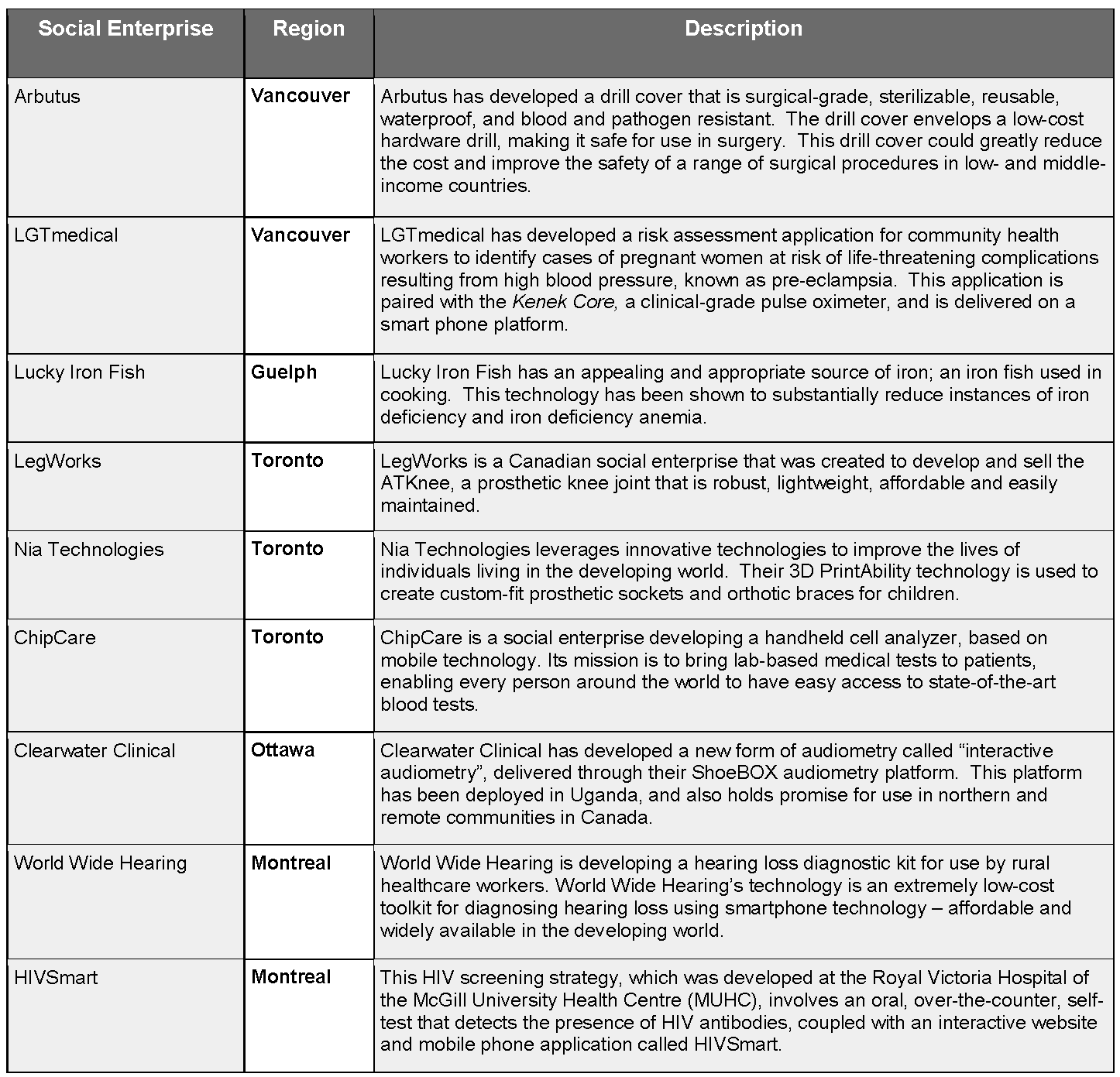

Examples of Canadian social enterprises supported by Grand Challenges Canada

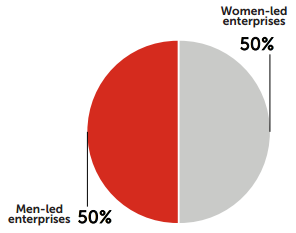

A further benefit from this increasing emphasis on social entrepreneurs is the increased participation from women-led enterprises. Currently, 50% of our Transition To Scale investments are in women-led organizations, which is significantly higher than comparator venture capital or impact investors. There are important qualitative distinctions between social enterprises that are led by women and those that are run by men. Women entrepreneurs bring different life experiences, tap into different networks, and tend to bring different points of emphasis to their work. We plan a more in-depth analysis of the impact of gender on our portfolio of innovations in the coming years but are encouraged by what we have seen so far.

Gender analysis of Grand Challenges Canada’s Transition To Scale portfolio

3. Source Widely and Scale Selectively

Successful innovation requires us to embrace smart failure. As our Scientific Advisory Board keeps reminding us:

“If none of your projects fail, then that means that you weren’t being bold and innovative enough in the first place.”

That being said, managing risk to cultivate success must always be foremost in the design of innovation programs. How do you ensure that failures cost little, occur as early as possible in the innovation process, generate lessons learned and lead to surer success in the future?

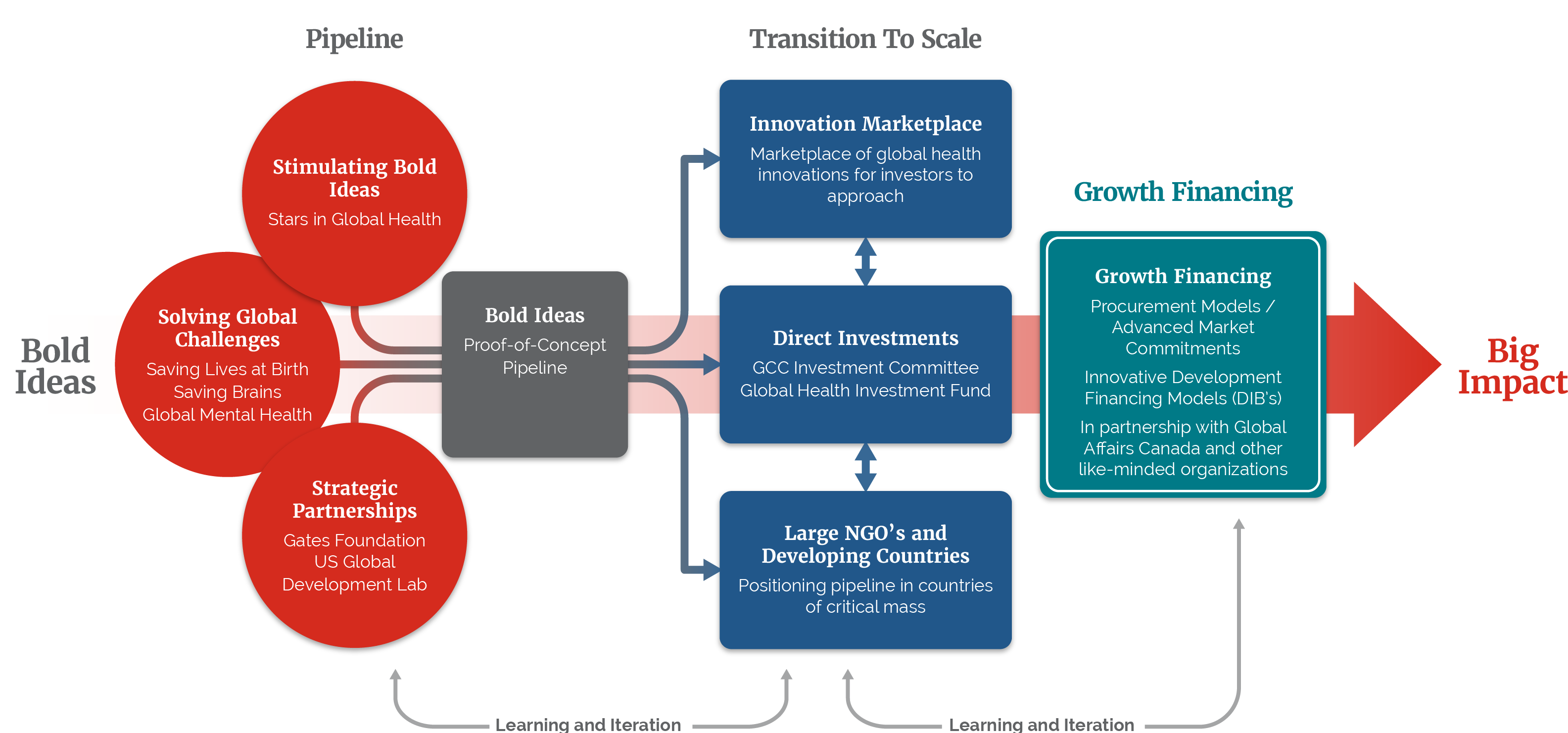

Our approach to managing risk is to source our innovations widely but scale very selectively. We welcome a broad range of potentially transformative ideas by sourcing and funding a large pipeline of innovations at proof-of-concept. We are very selective, however, in choosing innovations in which to make an additional or follow-on investment, based on our assessment of their potential for significant impact. We call this process of further investment “transition to scale”. In this way, we minimize risk and increase value for money by front-loading failures early in the innovation process, when they cost little, and then maximize success later in the more expensive stages of the process.

Grand Challenges Canada’s Innovation Process

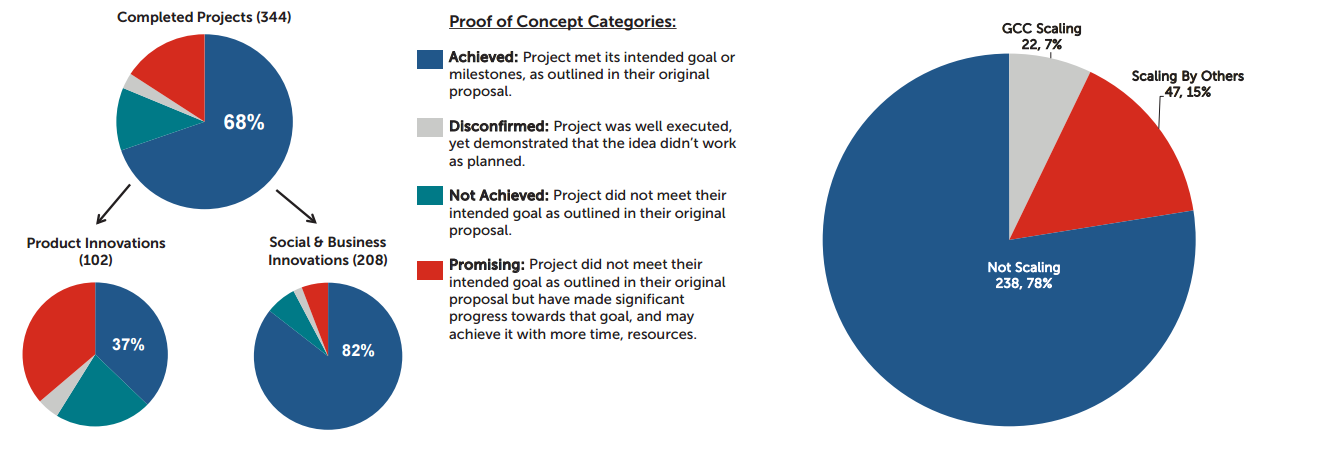

Happily, it appears that our approach to managing risk and increasing value for money is working as hoped. An initial analysis of our Stars in Global Health portfolio suggests that about two thirds of our innovators are achieving proof of concept with significantly higher success rates for social and business innovations in comparison with product innovations, as illustrated in the graphs below.

Currently, we are transitioning to scale about 7% of the completed projects from our Stars in Global Health program and about 10% of innovations across all of our programs. So what happens to the innovations in our pipeline that don’t transition to scale through Grand Challenges Canada? We have found that about 15% of our Stars in Global Health innovations transition to scale through external partners and channels. The balance of our innovations often produce new knowledge, evidence or policy change, which is valuable in its own right.

Left: Completed projects have been classified on the innovators defined proof of concept. Right: Breakdown of projects scaling by Grand Challenges Canada and others.

Having access to a sufficiently large pipeline of seed innovations is critical to the success of this model. Some of these seed innovations come from our own programs but, increasingly, we also look for promising innovations in our partners’ pipelines. The sharing of innovation pipelines and opportunities can be facilitated through initiatives like the Every Woman Every Child Innovation Marketplace. The Marketplace was launched in September 2015 under the United Nations Every Woman Every Child movement and the Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health, and is a strategic alliance of development innovation organizations, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Grand Challenges Canada, the United States Agency for International Development, and UBS Optimus Foundation. Although there is an increasing number of innovative healthcare concepts at the early pilot stage, a bottleneck exists at the “critical testing” ($250,000-$2,000,000 to further prove a transformative concept) and “transition to scale” ($1,000,000- $15,000,000) stages.

The Innovation Marketplace path to investment

The objective of the Marketplace is to make 20 transition-to-scale investments by 2020, and to see at least ten of these innovations widely available and having significant impact on women, children and adolescents by 2030.

To achieve these goals, the Marketplace conducts curation and brokering activities. Curation is comparative analysis of innovations sourced from partner organizations, while brokering is the process of matching promising innovations to the right investor. The Innovation Marketplace also creates value by convening stakeholders from the private sector, civil society and government to help ease the pathway of innovations to scale.

4. Emphasize Outcomes and Choose Smart Partners

At the heart of Grand Challenges Canada’s approach is identifying those innovations that are most likely to sustainably transition to scale and catalyzing their success. So what do we mean by success?

We have learned that it is critical to measure success based on outcomes, not just outputs. Of course, the challenge is that the outcomes of innovation are in the future, which makes them difficult to accurately measure.

At Grand Challenges Canada we have addressed this challenge by developing an approach that models the potential future outcomes of our most promising innovations.

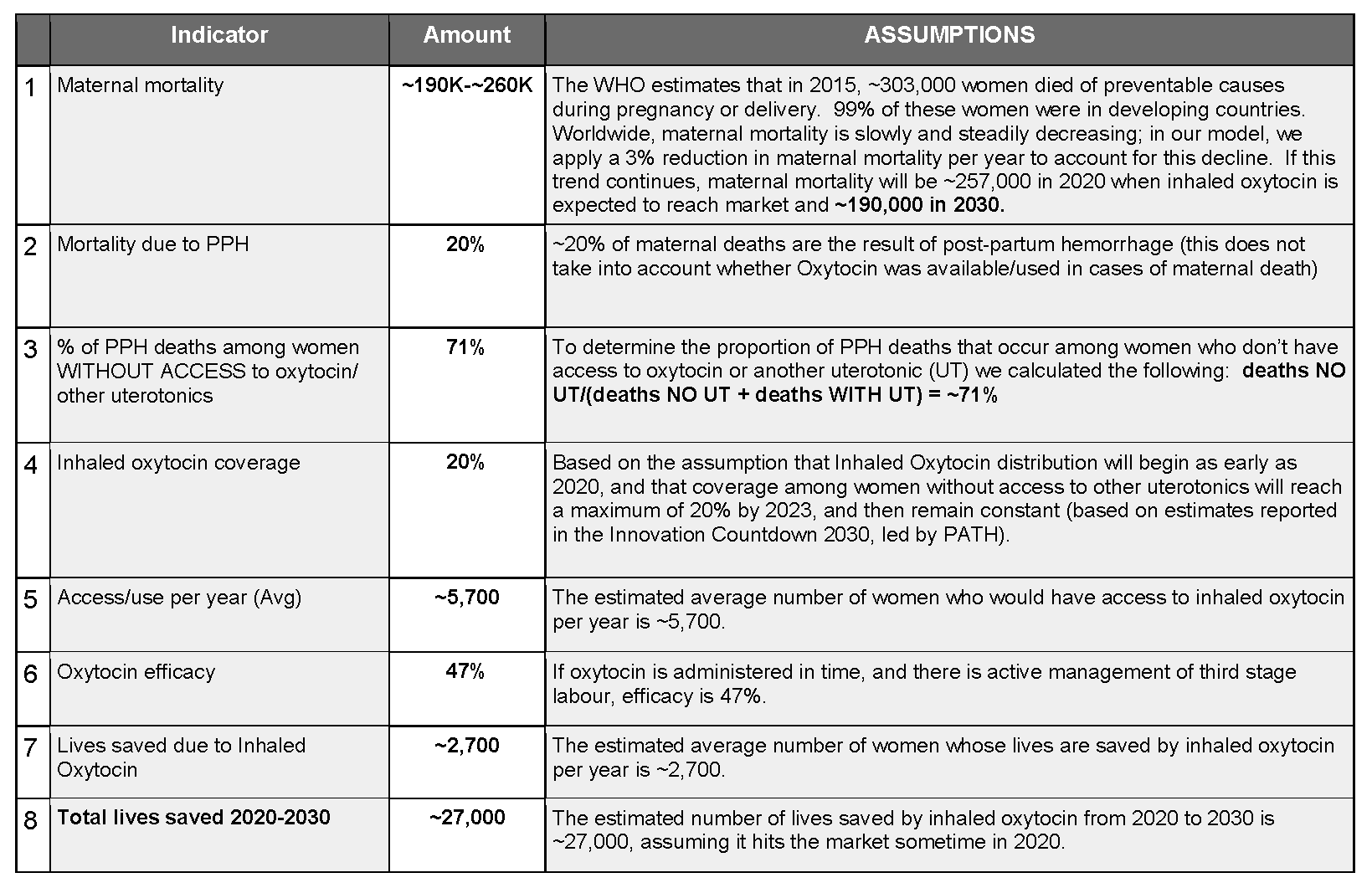

As with any model, our approach makes a number of assumptions that allow us to estimate potential lives improved – a key indicator for Grand Challenges Canada – as well as lives saved. An example of our approach to modeling, which we have developed with Results for Development Institute (R4D), can be seen in the following model that estimates the potential lives saved for a single intervention, inhaled oxytocin.

We are developing similar models (about 70 of them) for all of the innovations that we are supporting at transition to scale, and aggregating these potential future outcomes to get a sense of how our current investments can translate into the impact that we seek in the future.

Example of our approach to modeling

Now imagine expanding this work, building on common assumptions and taking into account economic and market factors, to all major innovation organizations and pipelines.

This would enable us to compare results, improve allocative efficiency and, ultimately, value for money. This would be an important first step to an outcomes-driven future for investments in innovation. As we often say, “innovation is the path and outcomes are the destination.”

This type of thinking will become increasingly important, given the critical role that innovation will play in the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals targets. We are committed to realizing this vision by sharing our work on outcomes measurement with our colleagues in other development organizations and institutions.

In addition, we achieve outcomes indirectly through changes in policies in low- and middle-income countries. Take, for example, one of our Stars in Global Health grants, which found that half of street food in Dhaka, Bangladesh was contaminated with pathogens. The project implemented a food safety education program that significantly improved hand hygiene and reduced bacterial contamination. These results were widely disseminated and contributed to the passage of the Safe Food Act 2013 and the Formalin Control Act 2015.

Another way to supercharge the model is to engage the right – or as we call them ‘smart’ – partners to work with our innovators. We call them ‘smart’ partners because they bring more than just money to the table; they bring leadership, governance, market intelligence, marketing knowledge and more.

Not every innovation can or should try to partner with the same types of organizations. We have found that promising social innovations, for example, have been successful at securing funding from not-for-profit organizations and domestic public sector partners in low- and middle-income countries. Similarly, successful scientific/technical and business innovations have attracted impact investors and successful social entrepreneurs as partners.

These partners play a crucial role in providing the expertise and “been there, done that” experience to help promising innovators to successfully transition their solutions to scale. While the right partners cannot guarantee success, they can help maximize the chances of lasting sustainability and impact.

Grand Challenges Canada and partners are accelerating development of an innovative inhaled form of oxytocin to manage postpartum hemorrhage after childbirth.

Take the example of inhaled oxytocin, mentioned above. Postpartum hemorrhages kill tens of thousands of new mothers every year. While an effective and well-established remedy exists — injectable oxytocin — it is unavailable to many women in resource-poor areas, due to highly demanding handling and storage requirements. Inhaled oxytocin allows patients to breathe the treatment through an aerosol delivery system.

Unlike the injection, the inhalant doesn’t require cold storage or administration by trained medical staff, making it available even to women who give birth in ill-equipped clinics or outside medical facilities altogether. This innovation, which has the potential to save 27,000 lives by 2030, was developed by Monash University and initially supported by a Grand Challenges Explorations grant and the Saving Lives at Birth partnership: A Grand Challenge for Development.

This innovation is now being accelerated through a collaboration catalyzed by the McCall MacBain Foundation with GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Planet Wheeler Foundation and Grand Challenges Canada. Beyond their financial contributions, GSK’s expertise in developing and producing asthma inhalers will be critical to this innovation’s success.

Finally, no innovation has ever scaled successfully without significant market demand. This is why country-led partnerships are so critical. A couple of our innovations have found their way into country health plans and this is, perhaps, the most important scaling partnership of all.

5. Mobilize New Resources For Scale

The challenges of global health and development are too big for any one organization or even sector to address. Certainly, when it comes to ambitions such as the Sustainable Development Goals, the public, private and not-for-profit sectors must collaborate to achieve progress. The Grand Challenges approach can aggregate and align contributions from civil society, domestic governments and the private sector. This is what Anne-Marie Slaughter refers to as ‘government as platform’. The potential of this type of approach is highlighted in the recent report Toward 2030: Building Canada’s Engagement with Global Sustainable Development, authored by Margaret Biggs and John W McArthur.

A good example of this ‘government by platform’ is the Saving Lives at Birth partnership: A Grand Challenge for Development, which brings together six partners that include governments, foundations and not-for-profit organizations, to overcome the challenge of protecting mothers and newborns and to prevent stillbirths in developing countries during the critical time around birth.

An important element of successful partnerships is to recognize and leverage the comparative advantage of each partner.

We describe our own unique comparative advantage as bringing the ability to “broker smart partnerships that mobilize private capital and domestic public resources”.

Over the past six years, we have also seen that social finance can play a critical role in mobilizing the kinds of resources needed to bring innovations to scale. We have learned, however, that social finance has the most impact when it uses public funding to catalyze not-for-profit, private and domestic government investment – crowding in and not crowding out investment.

An example of the power of public funding to crowd in capital is the Global Health Investment Fund. A $10M anchor investment from Grand Challenges Canada helped to catalyze a $108M fund that “provides financing to advance the development of drugs, vaccines, diagnostics and other interventions against diseases that disproportionately burden low- and middle-income countries.” To date, it has made six investments in companies that are scaling up rapid diagnostic tests (“RDTs”) for malaria, TB, HIV and other diseases; vaccines for diseases like cholera and drugs to treat conditions like river blindness.

There is also an important opportunity to strengthen funding from domestic governments in support of development innovation. For example, there are now more than a dozen domestic Grand Challenges initiatives around the world, including Grand Challenges India, Grand Challenges Israel and others.

These initiatives address a key component of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda on Financing for Development because they encourage countries to support their own innovators and mobilize domestic resources to support transformative health innovations. They also provide an important opportunity for Canada to engage with science and innovation leaders in low- and middle-income countries, in what is sometimes called ‘science diplomacy’.

6. Foster Reverse Innovation

Finally, Canada’s investment in the Grand Challenges approach has created an opportunity for what has been called ‘reverse innovation’. Ideas and innovations that work in low- and middle-income countries – saving and improving lives and reducing costs – can also be of benefit to Canadians. Take, for example, the development of a diagnostic ‘test and treat’ protocol using a rectal swab to manage acute diarrheal disease in children. A soft, brushlike instrument — the “flocked swab” — which was created for respiratory specimen collection was repurposed by a team at McMaster University and the late Daniele Triva of Copan Italia, for rectal sample collection. This flocked swab has been shown to provide samples that are better than either regular stool samples or traditional fibre-wound swabs for detection of treatable and potentially deadly pathogens, such as Shigella – all without waiting, mess or biohazard. And, at a very low cost per swab, it’s an inexpensive answer to a pervasive problem.

This innovation, developed by Canadian and Italian innovators, was tested and validated in Botswana but is now being trialed in northern and remote communities in Canada. The swabs are being used in Nunavut as part of the Rotavirus Gastroenteritis Surveillance Project. Researchers are hoping the information gathered with flocked swab testing will provide answers regarding how to best address and manage gastrointestinal illness in the territory, where children are two to four times more likely to be infected than in other Canadian regions. Over the next five years, our hope is to identify an increasing number of innovations that work in lowand middle-income countries that can be adapted to make a difference in Canada.

A child from Iqaluit, Nunavut, who benefited from the Grand Challenges Canada-supported project.

Two children from Botswana who benefited from the Grand Challenges Canada-supported project.

The flocked swab.

Concluding Thoughts

In their report, Innovation and Business Strategy: Why Canada Falls Short, the Council of Canadian Academies defines innovation as “new or better ways of doing valued things … An “invention” is not an innovation until it has been implemented to a meaningful extent.” I worry that in Canada, we focus on the first part of this definition and not enough on the second. If we are going to achieve the things that matter to us like the Sustainable Development Goals and their targets – it will not be enough only to have good ideas. We will have to figure out ways to transition these ideas to scale in a meaningful and consequential manner. I can imagine, and one day soon hope to see realized, the power of the Grand Challenges approach to help solve critical global challenges in areas like climate change. Moreover, the Sustainable Development Goals are universal and apply to all countries. I believe that the lessons of the Grand Challenges approach can also help to inform Canada’s, and other countries’, domestic innovation policies and practices.

Yours truly,

Yours truly,

Peter A. Singer, OC

Chief Executive Officer, Grand Challenges Canada

Twitter @PeterASinger

Previous Letters

2015 Annual Letter (pdf, 5.01 MB)

2014 Annual Letter (pdf, 9.35 MB)

2013 Annual Letter (pdf, 1.46 MB)

2012 Annual Letter (pdf, 3.00 MB)